Jack O'Connor's cartridge turns 100.

September 25, 2025 By Craig Boddington

John “Jack” O’Connor (1902-1978) was America’s dominant gunwriter for at least 40 years. Often called the “Dean of Outdoor Writers,” O’Connor was Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life for 31 years. Upon retirement in 1973, our founder Robert E. Petersen snatched him up as Executive Editor of the then brand-new Petersen’s HUNTING, his work gracing every issue until his sudden death, while on a cruise with his wife Eleanor.

Fellow gunwriter and rival Elmer Keith referred to him as .270 Jack. The O’Connor legend and legacy are inextricably linked to a favorite cartridge, the .270 Winchester, introduced in 1925, thus turning 100 this year. The .270 was an O’Connor favorite. He wrote about it a lot, especially in later years. So much that it was almost a personal talisman, his signature cartridge. However, it’s not fair to either man or cartridge to imply that the .270 was the only cartridge that had his blessing. The 7x57 Mauser was also a lifelong favorite, likewise the .30-06. In fact, in letters (never in print), he conceded the .30-06 was more versatile.

Elmer Keith’s rifle writing stressed larger calibers with long, heavy bullets. Mostly because he believed in frontal area—bullet diameter—for hitting power, and in bullet weight to ensure penetration. At least partly, because he despised Jack O’Connor, Keith hated the .270. Keith described the .270 Winchester as a “damned adequate coyote rifle.” The Keith/O’Connor rivalry is often described as a war of words.

In truth, it was a one-sided war, almost all on Keith’s part. There might have been tense moments when the two were together, like the large writer seminars held in those days. With his wry sense of humor, the Professor was likely amused but, in general, O’Connor neither responded nor participated.

O’Connor came to believe “his” .270 was perfectly adequate for game up to elk. To this day, some agree and others don’t. Keith grew up hunting elk in Idaho’s black timber, where shots were fast and presentations rarely perfect. He wanted big, heavy bullets that would penetrate deeply on the “raking” shots he wrote about. In the context of the close-cover elk hunting he was familiar with, he was probably correct.

What controversy remains regarding the .270 still centers around game larger than deer, elk being the argumentative centerpiece. O’Connor wasn’t a fan of more recoil than necessary; he liked the shootability of his .270. He also wasn’t afraid to step up when needed. The .375 H&H was also a favorite, used for brown bears in Alaska and for tigers in India. In the 1950s he used a wildcat .450 Watts (forerunner to the .458 Lott) in Africa. Later rifles included a .416 Rigby and a .450/.400 double.

The .270 was introduced in 1925 in the Model 54, Winchester’s first bolt-action. We customarily say that the .270 is based on the .30-06 case necked down. Technically, this is not correct. Winchester’s engineers used the earlier .30-03 case, longer by .046-inch, trying to wring out every bit of velocity. Which they did. The initial load used a 130-grain bullet rated at 3,140 fps. Perhaps optimistic; it was soon downgraded to 3,060 fps, still the standard velocity for the most common 130-grain load. Either way, a century ago that was fast. The .270 was the fastest American factory cartridge for some years surpassed only by the .300 H&H, coincidentally introduced in England in the same year.

In the late 1920s, young O’Connor owned an early .270. Apparently he didn’t fall under the new cartridge’s spell and didn’t keep it long. Lots of folks felt the same way. Initially, the .270 was not a runaway bestseller. The .270’s obvious intent was a cartridge that shot flatter than the .30-06, delivered less recoil, yet had credible power for deer-sized game (and maybe larger). The .270 delivered all this. Modest initial sales probably had little to do with the cartridge. At that time the .30-06 was unassailable, largely because surplus Springfields and U.S. Enfields were readily available and far cheaper than production rifles.

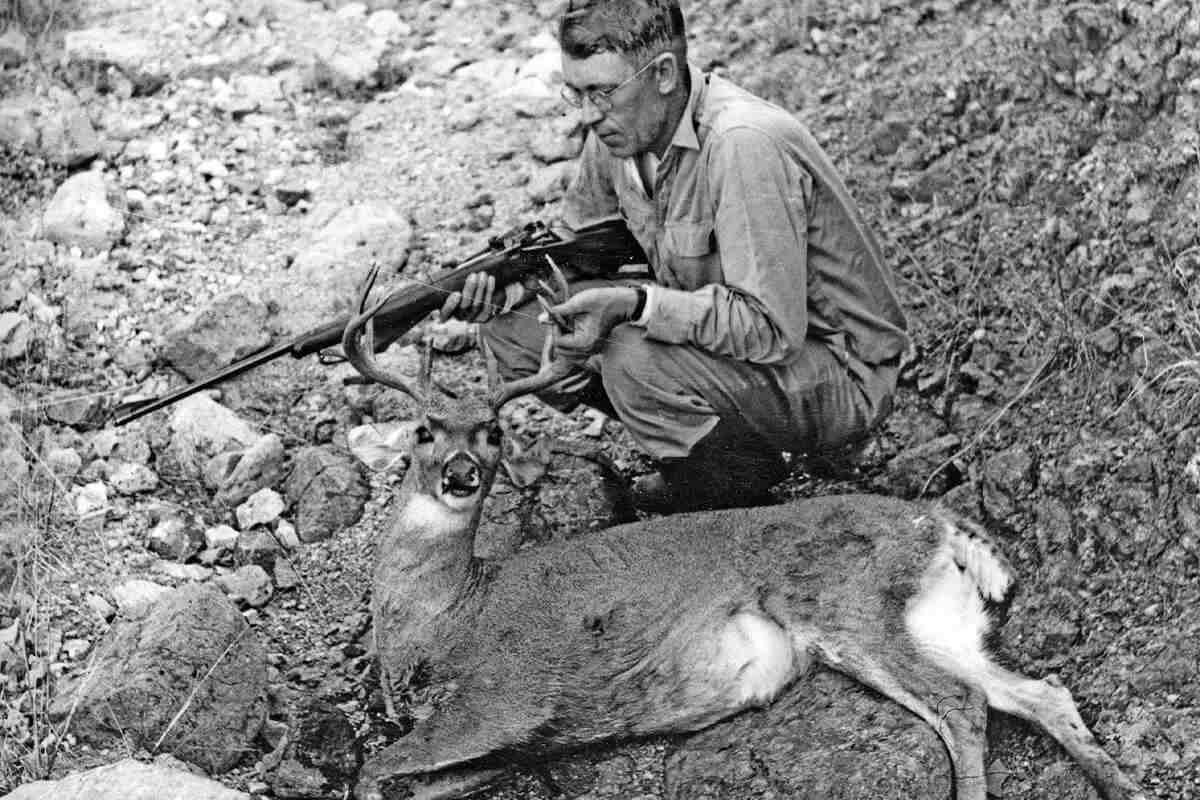

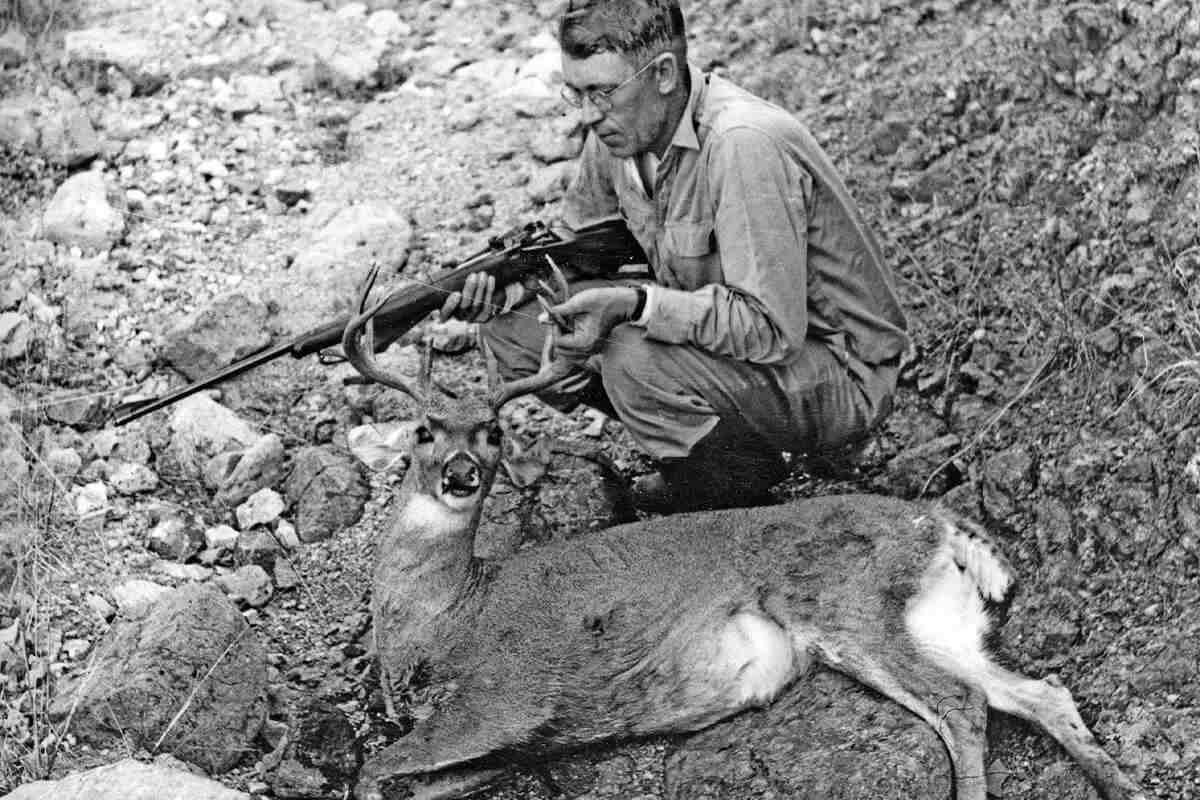

O’Connor’s first sheep hunt was in August 1935, hunting desert bighorn in Sonora. It was also the first sheep hunt for my uncle Art Popham, who was also a student of O’Connor’s. Art got rams (yes, plural is correct), but his teacher did not. O’Connor went back later that year and took the first of his many wild sheep. At that time O’Connor was between .270s. It’s not precisely clear how many desert sheep O’Connor took in Sonora. His first (and more) were taken with a 7x57. Later, a .257 Roberts and, as unlikely as it sounds, one with a .348 Winchester. According to his friend Buck Buckner, only his last Mexican ram fell to a .270. That was just after WWII, and by then O’Connor had become a .270 fan, though not as staunch and steadfast as he was in later years.

To some extent, it was rifles, not the .270 itself, that upped the ante. In 1954 he had a gorgeous rifle on a Winchester M70 action, in .270, stocked by Al Biesen to his taste and fit. He used it for elk, smaller game in India and mountain game in Iran and found it perfect. Five years later, O’Connor bought a new Winchester M70 Featherweight .270 at Erb Hardware in Lewiston, Idaho. I find this interesting. We gunwriters are notoriously thrifty (read: cheap). Surely, he could have called his friends at Winchester and asked them to send him one, find out if it shot, then decide to buy or return.

He did not. He bought this one off the rack and discovered it grouped under one MOA. This level of accuracy was unusual in a factory rifle 60 years ago. One assumes it grouped tighter than his current favorite. He took it to Al Biesen in Spokane, asked him to stock it similarly. The result was still super-accurate in its awesome new handle. It quickly became a favorite.

He dubbed it Sheep Hunter No. 2. We know it better as Biesen No. 2, used as the inspiration for the O’Connor Tribute limited edition M70 Featherweight, commemorating the 75th anniversary of the M70, the “Rifleman’s Rifle.” O’Connor used his original No. 2 extensively (not exclusively) for the rest of his life. In Africa, back to Iran and most of the mountain hunting that remained. It accounted for his last ram, a Stone sheep in British Columbia, in 1974. And he carried it on his last hunt, for whitetails in Montana in the fall of ’77, with old friend and mentor Jack Atcheson, Sr.

O’Connor never saw a synthetic sporter stock, so he dragged and dinged his Biesen rifles in beautiful French walnut up and down sheep mountains. He also never saw today’s efficient unbelted cartridges, although he saw many brave new magnums come and go. He believed in the .270, never found it wanting. I suspect he used it as much as he did because he loved his Biesen rifles as much as he loved the .270.

On early northern hunts in the 1940s, he often took two rifles, a .270 and a .30-06. Partly to have a spare, and because he knew the .30-06, with its heavier bullets, was better-suited for larger game. On most of those hunts, the primary game was sheep. Back then, everything was open and bag limits were generous. O’Connor took multiple moose and grizzlies with his .270s. I have never implied from his writing that he thought the .270 was ideal for such game. Rather, he was hunting sheep and used what he carried when opportunities arose. On elk, he was unequivocal: His .270 was enough gun. A careful marksman with long experience in high-power competition, it was certainly enough gun for him.

As a kid, I worshipped O’Connor as a distant deity, but I also read Elmer Keith. As a younger hunter, I questioned the .270’s efficacy for elk and larger game, often coming down on the Keith side of the argument. However, in a letter (never in public or in print), Keith conceded that a .270 with 150-grain Nosler Partition (the only premium bullet of their day) was acceptable for elk. Both were correct.

Over the years, now using tough, deep-penetrating modern bullets, I’ve seen .270s work just fine on elk and other large game. Even so, I still think the .270 is best-suited for deer-sized game. Meaning: all deer, mountain game and medium African antelopes. For larger game, up to elk and zebra, it’s marginal, but on the right side of the margin. My wife Donna is more of a .270 girl than I’m a .270 guy. She’s taken most of her game with her light MGA .270, including elk, Asian wapiti, larger African game up to zebra, and all of her wild sheep and goats. Consistent results.

Although still popular, with so many new cartridges and so much hype, I think the .270 is becoming misunderstood. Just this past week, one of my Kansas deer hunters stated that he understood the .270 and the 6.5 Creedmoor were similar in power. Uh, no. Standard .270 loads include a 130-grain bullet fired at 3,060 fps, a 140-grain bullet at 2,950 fps and a 150-grain bullet at 2,850 fps. All three loads produce about 2,700 ft-lbs of energy at the muzzle. Although wonderfully efficient, in its shorter case the 6.5 Creedmoor runs about 2,700 fps with a 143-grain bullet. Energy yield is 2,283 ft-lbs., or about 15 percent less energy than the .270. Doesn’t sound like much. In my opinion it’s too much to lose. Because, if the .270 is marginal for larger game (such as elk), then the Creedmoor is below the margin. Fine up close, not enough energy at distance.

In the 1920s, when elk and even deer populations were low, centerfire rifle competition was perhaps even more popular than today. Even so, the .270 was conceived as a Western hunting cartridge. Fast, flat-shooting, no pipsqueak, but with tolerable recoil. Never envisioned as a match cartridge, until recently almost all .277 bullets were hunting projectiles.

This suggests that accuracy isn’t the .270’s strong suit. I have never found this to be true. Maybe it won’t set benchrest records, but I have rarely seen an out-of-the-box .270 that didn’t shoot well. Few that were finicky about loads, and some that were tack-drivers. Donna’s super-light MGA .270 is one of these. So are my .270s, a .270 barrel for the Blaser, and a beautiful custom rifle on a left-hand Carl Gustav action, built by Joe Balickie decades ago. Interestingly, the most accurate production .270 I’ve grouped was a Jack O’Connor Tribute, quarter-inch groups right out of the box.

In 1925 scoped hunting rifles were uncommon. O’Connor himself didn’t hunt with a scope until about 1940, and he never saw a laser rangefinder. The 1,000-yard competition was popular, but no one envisioned today’s extreme-range shooting. In the field, what we thought of as long shots were much shorter than today.

So, the .270 was developed as a hunting cartridge, maximum velocity and good performance on game out to a quarter mile, maybe a bit farther. Serendipitously, that distance is my comfort zone for shooting at game (provided conditions are right). Sight an aerodynamic 130-grain spitzer at 3,060 fps 1.5 inches high at 100 yards to be zeroed at 200. From there, about 6.5 inches low at 300 yards, 20 inches down at 400, and a bit over three feet at 500 yards. For those who do their homework and dial the range, trajectory is just a number.

Despite all the stuff we read and hear these days, 400 yards is a long poke on game. I’ve taken a lot of game at that distance, and beyond, with .270s. However, for today’s extreme-range crowd, older .270s—.270 Winchester, Weatherby Magnum, and WSM—don’t measure up. All were specified for 1:10 twist (same as older .30-calibers). In 1925, Ballistic Coefficient (BC) was known science, ballistic advantages of boattail spitzers also known. Today’s longer, heavier, low-drag projectiles didn’t exist. In .277 diameter, the 1:10 twist maxes out at 150 grains, and that 150-grain bullet better not be too long. Fans and naysayers alike have long complained that the .270’s greatest flaw is its lack of heavier bullets. Heavier hunting bullets would be better for larger game. Heavier, low-drag target bullets would put the .270 back in the long-range game. All true, but not possible without faster-twist barrels.

These bullets now exist in .277, and they are the basis for “new” .270s, including the .27 Nosler and 6.8 Western, specified for faster twists. Back in the 1960s, Jack O’Connor stated: “the 7mm Remington Magnum couldn’t do anything my .270 can’t do.” Almost true. I believe in frontal area for transferring energy, but the difference between .277 and .284 (seven thousandths) is too close to argue about. However, on larger game the .270’s 150-grain bullets can’t equal the 7mm’s 175-grain (and now heavier) bullets.

The new .270s with fast twists and heavier bullets change the game. They also kick more. If you want to use those new heavy bullets to expand your range envelope, you can always rebarrel. Fast-twist .270 barrels aren’t new. Me, I like my .270s as they are. They can ring steel at long range, and I set my own limits for field shooting. The .270 Winchester performs well within my limits. The older I get, the more I think Professor O’Connor was right all along: The .270 Winchester is a wonderful choice for sheep, goats and all deer-sized game. And somewhat larger if you’re careful. I have other tools for larger game. Although the cartridge is now 100 years old, I’ve only been using it for 50 years, but don’t see any reason to stop.